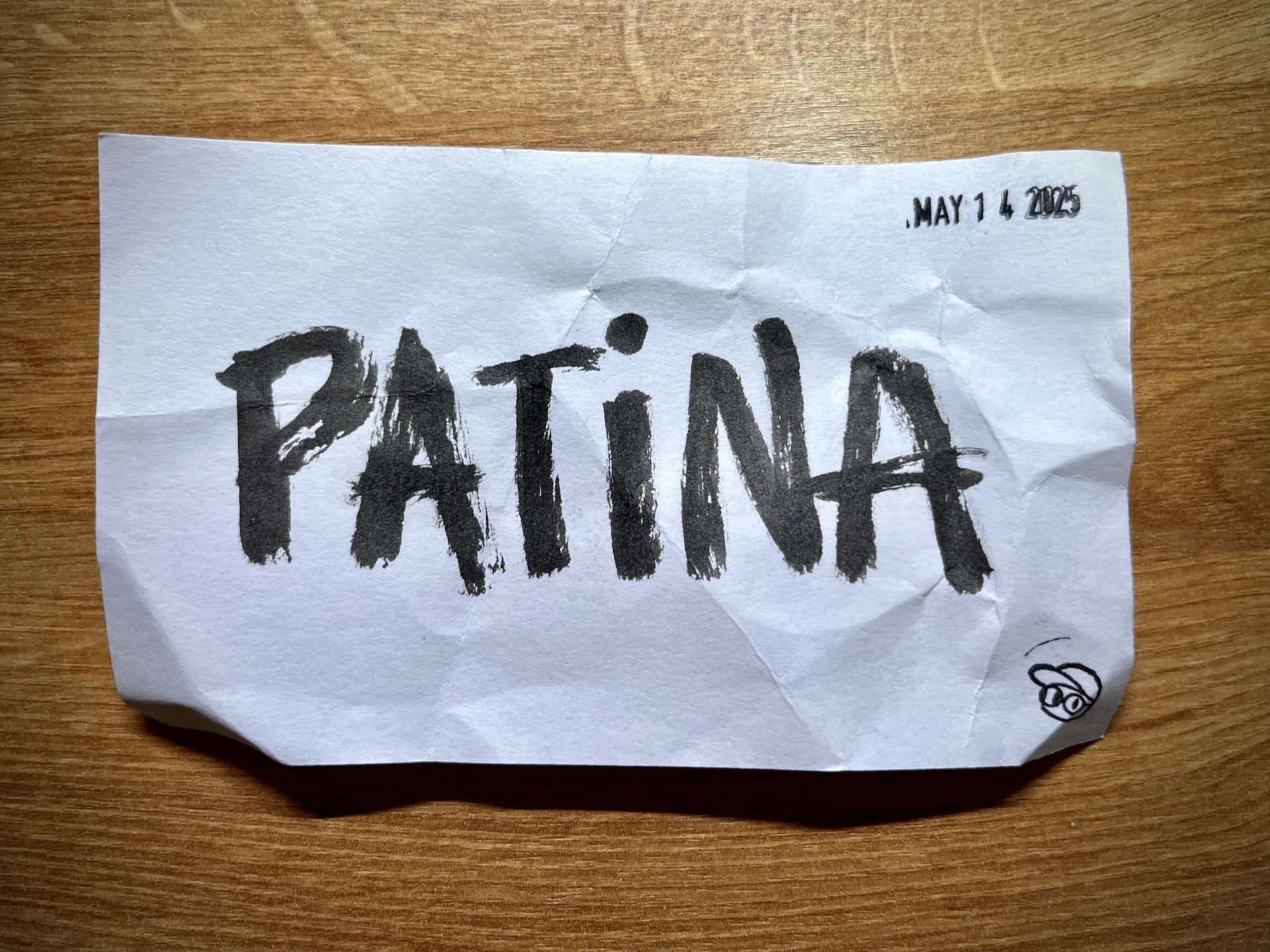

Things with patina have been used. And things that get used were once useful — even if they no longer are.

That’s the story patina tells: not of decay, but of service. Of purpose. Of a life lived.

Pristine

I used to be obsessed with pristine. Everything had to be perfect. Clean. Untainted.

Especially notebooks. The expensive ones — the Moleskines, the hardcovers, the beautifully bound ones I bought but never filled. Or barely filled. I didn’t want to “ruin” them with a bad idea. A sloppy drawing. A page I’d regret.

It made even a simple scribble feel like sacrilege. So I didn’t use them.

That pressure to preserve the pristine didn’t stay on the page. It crept into my design work. I held back ideas that weren’t “ready.” Polished pixels for too long before sharing.

I spent too much time — too much unnecessary time — obsessing over pixel perfection instead of focusing on problem-solving and collaboration. I confused perfection with professionalism . As if making things look pretty and polished was the heart of design. I was playing into this pretentious, pervasive idea that unless something was perfect, it didn’t count. That if it wasn’t flawless, then you didn’t really care.

Over time, I started to fight back. Not with big declarations — but with small, practical rebellions.

- I handwrote labels instead of using a label maker.

- I forced myself to write in the darn notebooks — in pen. (No erasing. Learn to live with it.)

- I kept the cracked screen protector on my phone. Intentionally. (Ugh, I know!)

Little by little, I chipped away at my perfectionism — by letting my things show their age.

Dirt

A couple of years ago, I watched an interview with James Dyson, where he shared his philosophy on design — including the now-famous story of how he built 5,127 prototypes before landing on the vacuum that worked. He spoke about persistence. Learning. The importance of not giving up.

He also told the story of his first vacuum — the one with the clear, see-through canister. At the time, it was considered a terrible idea. The marketing team hated it. Why would anyone want to see the dirt? Wasn’t that the opposite of “clean”?

But Dyson stood firm.

“Seeing the dirt is honest,” he said.

And you know what? He was right. That vacuum went on to become a massive success. And now? Nearly every modern vacuum proudly shows you what it picks up.

That line — seeing the dirt is honest — stuck with me.

It gave me permission to let go of the pristine. To embrace the patina. To not just tolerate wear and tear, but to see it as a story. As evidence of usefulness.

Not something to hide. But something to be proud of.

Debt

In software development, there’s a term for past code and decisions that were once helpful but now feel like they’re holding everything back.

That term is technical debt — or “tech debt” for short.

It’s the thing we all love to point at. To roll our eyes at. To mock, despise, and blame. It’s the scapegoat for why things feel slow. Why things feel hard.

But here’s a reality check:

Without that tech debt, you probably wouldn’t have a product. And without that product, you probably wouldn’t have this job.

That messy code? Those clunky decisions? They were made by people trying their best — trying to make things work and keep things moving, with the time, tools, and context they had.

Tech debt is the patina of your product. Its a mark of it’s makers. Of progress. Of life.

You’ll never be rid of it entirely — and that’s not the goal. The goal is to understand it. To see it clearly. To clean it up when you can. And if you have the privilege to spot the mess — and the capacity to make it better — then please do. Leave behind something just a little better than what you inherited.

Because today’s improvements? They’re tomorrow’s patina.

Patina

These days, I buy things in white — when I can.

Not because white feels pure — but because it gets dirty faster. It shows the scuffs. The scratches. The pen marks. The fingerprints. The wear. It shows where something’s been. What it’s been through. It shows that I used it.

It tells the story of its usefulness.

Right now, I’m looking down at my keyboard. You can see the patina on certain keys.

The “Command” key, naturally. The “A” key. The “S” key. The “C” key. And — mysteriously — the “L” key?

These little worn-down letters tell a story. A story of muscle memory. Of repetition. Of how I use computers. Apparently… I’m a compulsive select-all-copy-and-saver.

But that’s the point. The patina isn’t damage. It’s data. It’s proof of use. Proof of care. Proof of craft.

Celebrate the patina of everyday things — because every defect gets respect.