When I’m making something — or solving something — what I’m really optimizing for is this:

To figure out, as quickly as possible, the shape of the world I’m working in.

Fog

In video games, especially open-world ones, that world is literal. It’s the overworld — the map that shows the terrain you’ve explored and the parts still covered by fog. The fog of war.

You load in. The map is blank.

There’s one little blinking dot where you’re standing, and everything else? Hidden. Blacked out. Unknown. Undefined. Maybe dangerous. Maybe boring. You don’t know.

That’s what most projects feel like.

There’s a goal on the horizon. A deadline in the distance. And a vast, unexplored space between here and there. Our job is to chart it. To name the regions. To find the edges of the map.

You can’t wait for clarity before you move. You have to start sketching the map as you walk it.

Because when you’re deep in the unknown, clarity isn’t just for planning. It’s for managing anxiety—giving shape to chaos, so you (and others) can move with a little more calm. A little more confidence.

We’re usually not afraid of the task. We’re afraid of the not-knowing. So draw the knowing. Make it visible. Even if it’s rough. Even if it’s wrong.

There’s power in seeing it come together—even if it’s scrappy.

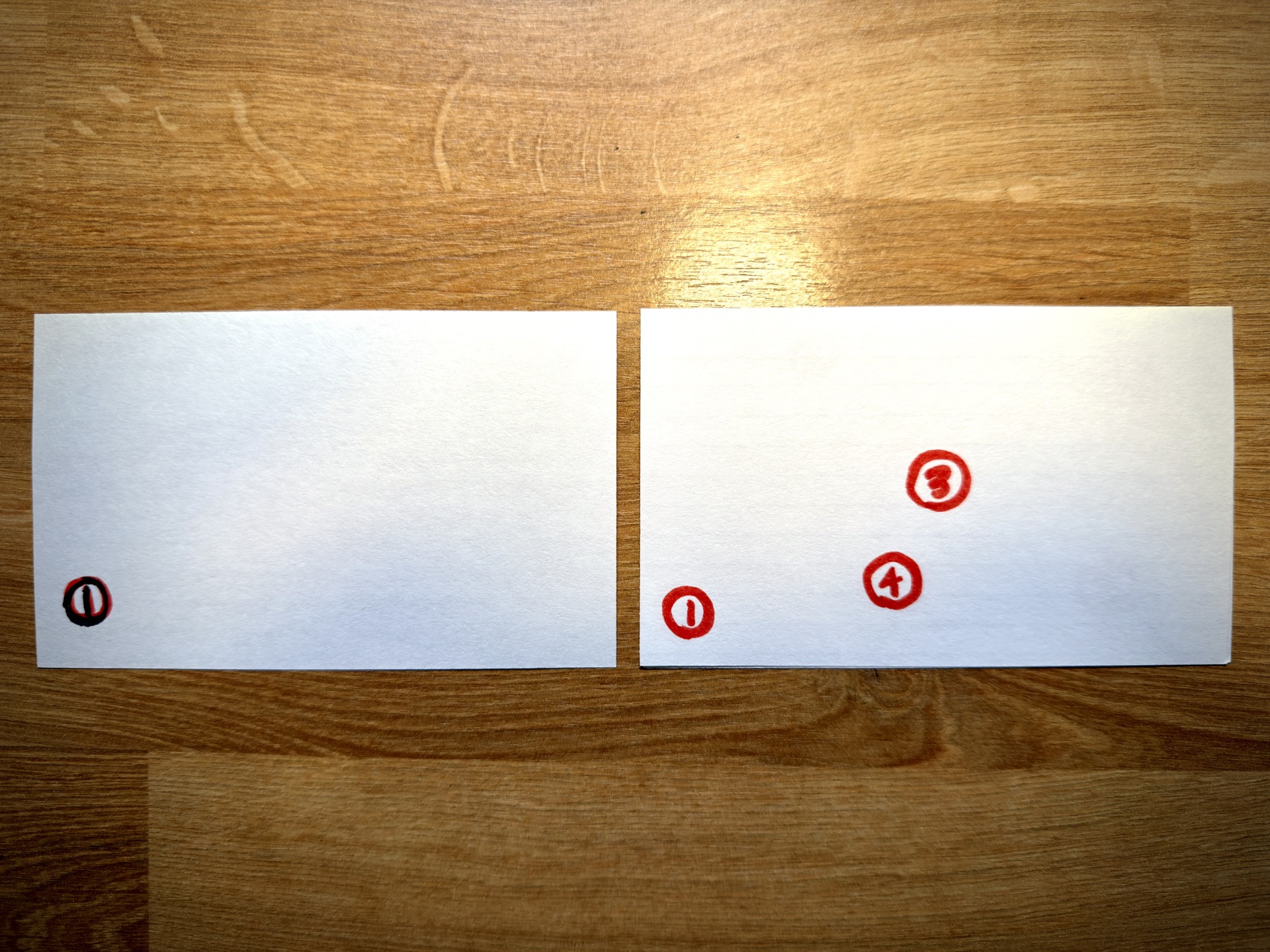

Regions

Problem-solving isn’t linear. I never start with “Step 1.” I start wherever the terrain feels clearest — maybe that’s Step 3 or Step 7.

Once I find one landmark, I don’t linger to polish it. I look for the next. Then the next. Out of order, messy, quick. What matters most at the beginning isn’t quality — it’s coverage.

I keep sketching until I can sense the outline — until the fog starts to pull back and I can say, “Okay, this is the shape of the problem.”

It’s like an artist roughing out the first ovals and rectangles of a character sketch. Loose, gestural, imperfect. You don’t know the full form yet, but you know enough to keep going.

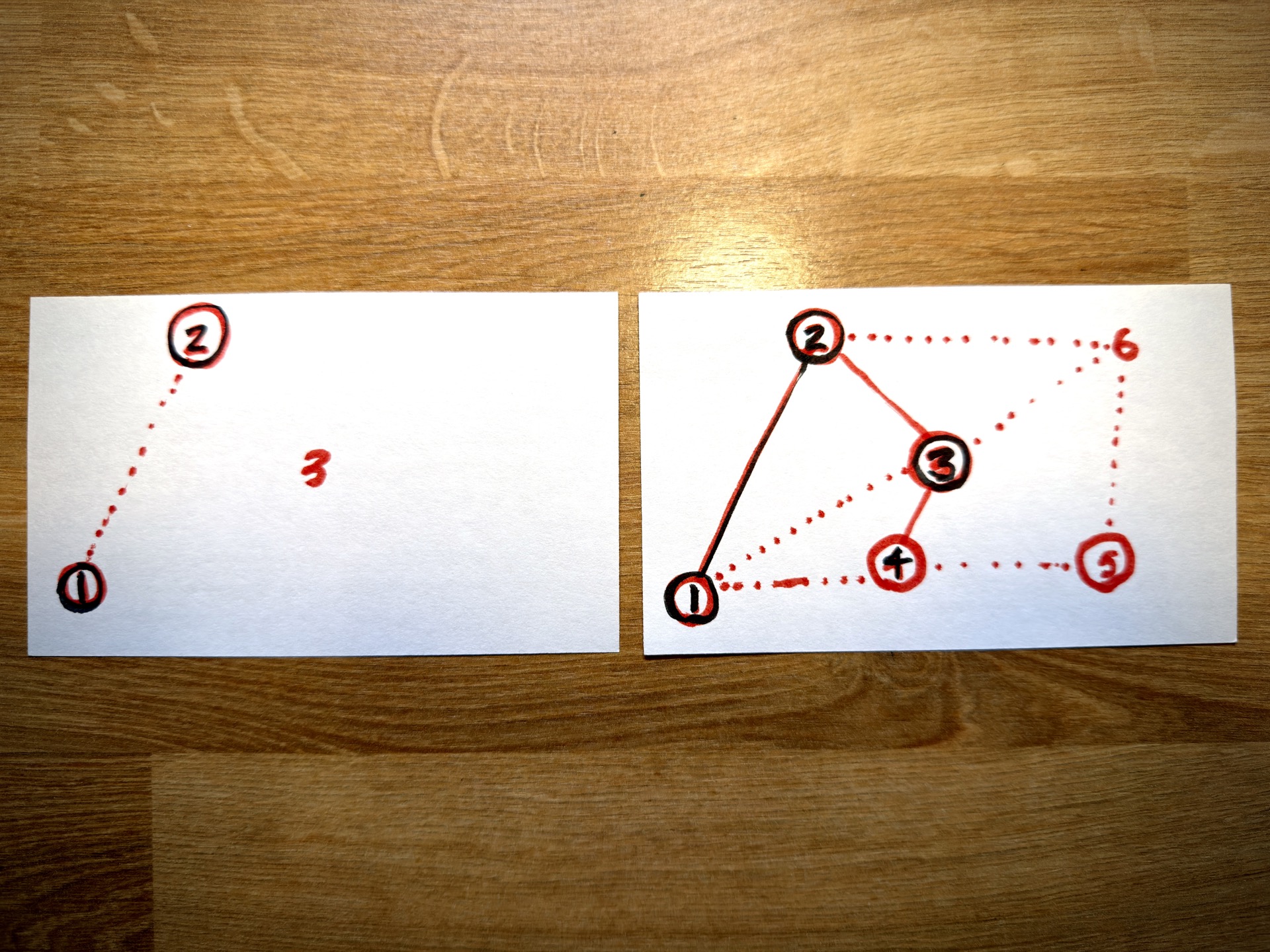

Roads

Once the shape is there, I start to connect the regions. See what fits. What doesn’t.

This is where it starts to feel like something real — not complete, not final, but alive.

As you refine, unexpected connections appear. Some are useless. Some unlock everything.

It’s all part of filling in your overworld.

And even if the total “progress” bar hasn’t moved, the feeling of progress has. You and your team can finally see the world you’re building. You can talk about it. Touch it. Believe in it.

Realization

One of the projects I used this method for was Webflow’s Interactions with GSAP — a wild, ambitious, moving target of a thing.

Early on, I told the team: “I just want to see a rectangle dance in Designer.”

That was our first landmark. The moment the fog started to lift.

And once we got there, the goal evolved: “Now I want to see the rectangle dance in interesting ways.”

Sometimes you have to go deep — building the technical foundations, layer by layer.

Other times, you just need to make something move — to help people believe it’s possible.

It’s not about figuring it all out at once. It’s about seeing just enough to take the next step — and giving others the confidence to step with you.

Because once you can see the world — even roughly — you can move through it. You can map it. You can make it real.